Section A Vignette #8

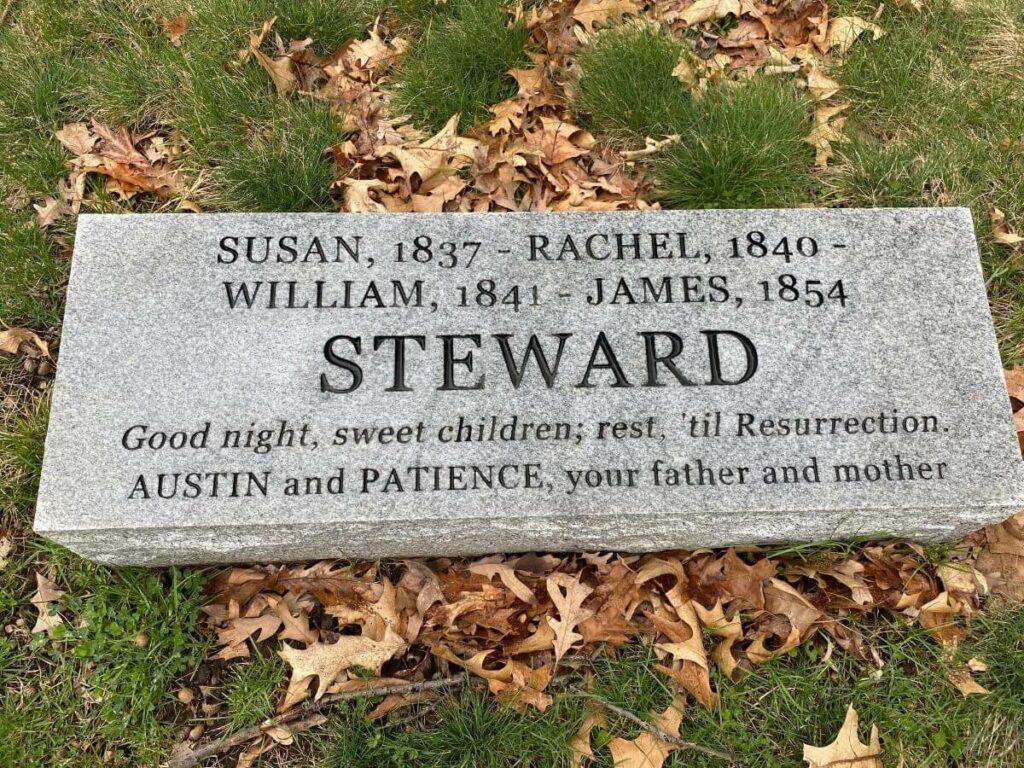

In the northwest corner of Mount Hope Cemetery lies a gravestone marking the burial plot of four children. These are the children of Austin and Patience Steward, three of whom died in infancy and one, Susan, who died at age 11. For many years the grave was unmarked until a committee led by Dr. David Anderson purchased the headstone and placed it on the site.

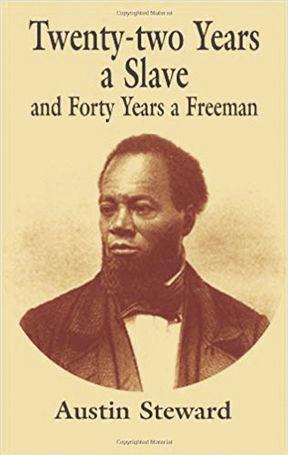

Why are these four Steward children buried in Mount Hope when their parents and five of their six siblings (excluding Barbara) are buried at the West Avenue Cemetery in Canandaigua? Are all four actually interred in Section A? Was Susan buried prior to the 1838 dedication of Mount Hope as her father reported in his autobiography Twenty-two Years a Slave, and Forty Years a Freeman?

We may never learn the full answers to these questions, but much is known about Austin Steward and his life-long dedication to the abolitionist movement and to the betterment of all Black citizens.

Austin Steward was born into slavery in Virginia—the property of Capt. William Helm. When Steward was a young boy, Helm was forced to sell his plantation to cover his gambling debts. Helm then took his slaves to the Sodus Bay area in upstate New York. To bring in additional income, Helm rented out his slaves to work at neighboring farms. It was at this time that Steward realized that the North provided more liberties to slaves and began to think more deeply about what his future might hold.

Because Austin Steward had taught himself to read using an old spelling book, he was well-positioned to flee Helm’s grasp with the help of the New York Manumission Society and the Quaker community. They told him that because Helm had hired him out, Helm had forfeited legal ownership of him—a technicality in the state’s Gradual Emancipation Statute.

By his early 20’s, Steward owned property in Brighton and was a successful merchant. He was also becoming an active participant in the anti-slavery movement. Within ten years, he had married Patience Butler from Canandaigua. It was not unusual for children to die in infancy and this was the sad fate of three of the Steward children: Rachel, William and James. They are all buried in Mount Hope Cemetery. The first born Steward child, Susan, died at age 11. Austin Steward wrote that she was also buried in Mount Hope, but cemetery records don’t verify that account. The remaining Steward children all lived into adulthood, except for Patience who died in her late teens.

In 1830 Austin Steward took his young family to Canada, intent on establishing a colony to support fugitive slaves from the United States who were trying to secure their freedom in Canada. He closed his meat market and grocery business and once in Canada started Wilberforce—named after William Wilberforce, who had worked to help abolish the slave trade in England. The Stewards lived and worked there for seven years, and during that time Barbara and Sarah were born. Ultimately, the colony lost funding and the Stewards were forced to leave Canada, nearly destitute. The family returned to Rochester, but then moved to Canandaigua, Patience Steward’s hometown. It is suspected that Susan died on the returning trip. Steward re-established his business in Canandaigua and continued his work with anti-slavery groups.

Of all his children, Barbara appeared to have taken up her father’s anti-slavery causes. She was well-educated and is said to have worked closely with Frederick Douglass. Barbara was a strong supporter of industrial schools, believing that they would be beneficial to her race by expanding employment opportunities. She believed that mere knowledge of books without a trade of some kind was almost useless. Barbara was a typical “middle child”—fifth born of ten. Given the size of the family and perhaps her gender, she may have been under-appreciated by her parents, but she was driven to prove herself worthy and showed independence and a sense of individualism. At the age of about 20, Steward addressed the Meeting of Colored Citizens in Rochester on the rights and wrongs of her suffering people. Afterwards she was praised by Frederick Douglass’ paper for her zeal, devotion, character and ability in speaking out for enslaved women who couldn’t advocate for themselves.

Austin Steward and his wife Patience spent the rest of their years in Canandaigua, out-living all of their children. While they and five of their children are buried in Canandaigua, there remains a link to Rochester with the plot in Section A where four others are memorialized. Barbara’s final resting place remains a mystery, even though she died a decade before her parents. This is curious, given her significance as an advocate for equality.

Nevertheless, Austin Steward and his daughter Barbara were both dedicated to the anti-slavery cause and should both be remembered for their contributions to the freedoms deserved by all citizens.

Wendy Heffer